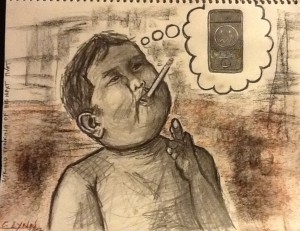

I drew this especially for this post. Remember that viral video of the 2-yr-old Indonesian kid smoking a cigarette? Here he is in his extrastructural boredom thinking of his next pivot.

Smartphones are like cigarettes are like junk food are like chewing your nails or doodling. Right. What do they have in common? Easy. Things we do when we’re bored. Bored in my class? Doodle. There were some amazing Jurassic landscapes drawn on quizzes in my “Evolution for Everyone” class last semester. Can’t sit idly waiting for the red light? Chew your fingernails until the edges bleed. Commercials got you down? Good you keep a bag of chips handy & a bowl full of M&Ms. Is our conversation too much of me talking & not enough about you? Step outside & have a smoke break in the monotony of our friendship. Does the naked space of your own mind & the world around you send you screaming into oblivion when you walk across campus, across a street even? Pull out your smartphone & check your email again–that car will swerve around you.

I am being facetious…& of course I am not. All these little things we compulsively do when it would be nice if we were paying attention are annoying when you’re on the other end of them, but this isn’t one of those preachy what-has-the-world-come-to those kids with their smartphone-doo-hickies I-remember-when-we-thought-a-rotary-dial-was-newfangled rants. ( I am currently desperately seeking to upgrade to an iPhone myself.) No, no, I’m far more interested in how smartphones “superstimulate” our evolved compulsion to “play” at all the “extrastructural” interludes of our lives — i.e., when we’re “bored.” I love the concept of cultural structures or objects superstimulating our cognitive architecture because it simultaneously stimulates a variety of mechanisms that evolved for other purposes. Pascal Boyer uses this concept to outline the by-product model of religion (read a 2008 summary article in Nature here). I think many successful memes are so because they simultaneously please us in so many ways. Television superstimulates us, as do computers (with high-speed internet), & now smartphones. Smartphones do so by both serving as a fantastic “prop” (Walton 1990) or “pivot” (Vygosky 1978) — “an object that facilitates the transformation into the space of play” (Stromberg, Nichter, & Nichter 2007:17). Smartphones are pivots around which we can navigate extrastructural space — both real space & virtual space — while providing us with an assortment of other pivots. And all the advertised features of smartphones are pivots on their own accord, from the phone to music to games to books — they are all things we do in our “free” time, when we’re bored, or are otherwise subject to unstructured space.

“Extrastructural” space refers to what Stromberg et al. define as “social situals that lie outside the structure of the mundane and everyday” (2007:5). For instance,

Parties, stress, and boredom are all instances of peculiar moments in social life that lie outside the demand strcuture of everyday life…[whereas] on most days we enter and exit institutions that contain fairly circumscribed activity domains such as jobs or classes. Then there are other, often less structured, contexts that nevertheless impose, for reasons of function, tradition, and so on, demands on actors: eating and sleeping, engaging in entertainment activities, or studying. However, there are also situations that lie significantly outside the structure of the everyday and are often recognized as such: the break, the vacation, the celebration, the moment in which there is nothing to do, the situation when demands are so great that one’s unthinking compliance to the routine begins to break down. (2007:5)

It is in response to such unstructured time that unscheduled play enters the picture in “improvisational forms” (2007:6). Play typically involves some rules, particularly in the case of certain games, & thus extrastructural situations are not wholly without structures, as play imposes structure on the interstitial space “to substitute for that which is missing” (2007:6).

I began riffing on this halfway thru this past semester when (1) either the smartphone texting came to a critical mass in the midst of my lecturing or (2) I started to take more notice & umbrage. Maybe it’s because I’ve been growing the course, maybe it’s attracting a less interested general audience, maybe it’s me…No, no, it’s the “Anthropology of Sex.” It’s hard to kill the interest in that class. I have my days, but not EVERY day…I had brought up Peter Stromberg’s 2007 Culture, Medicine, & Psychiatry article with Mark & Mimi Nichter, “Taking Play Seriously: Low-Level Smoking among College Students,” in an Honors seminar I teach called “Primate Religion & Human Consciousness,” made a smartphone connection, & then noticed them popping up like so many Bics being flicked at a golden oldies reunion concert. “Youth live in an age of increasing time compression, greater opportunities for arousal and diminishing tolerance for boredom, and the proliferation of products that promise instant gratification (Starace 2002),” the authors point out (2007:7). As I say, I have resisted the “these young people today” sentiments, but perhaps there is something to it. Stromberg, who has written the book Caught in Play: How Entertainment Works on You & writes a blog for Psychology Today called “Sex, Drugs, & Boredom,” draws on the evolution of play literature to frame young adult cigarette smoking behavior as “play,” & I find myself quite taken with this idea.

Developmentally, play is how we build & test social contingencies or “scenario-build,” as Richard Alexander laid out in his seminal article “Evolution of the Human Psyche.” Playing is how we superficially test scenarios & test the boundaries of safety, both in social relationships & reality. So I pose the question, what do you like to play? Would anyone say, “I like to play with smoking cigarettes”? What is the difference between saying, “I like to play knife- & ax-throwing” (which I had just done at a Renaissance Faire-type event) & “I like to play cigarette smoking”? Both are adult forms of boundary-pushing, safe in moderation & controlled settings but potentially dangerous. Both can make a person look cool if done right or a ridiculous caricature if not. And then if I’m a knife-thrower, when I’m not throwing my knives, what do I do with them? I may try to keep them safely in my…(what? pants pocket?)…er, I may find myself picking my teeth with them, cleaning my nails, even while I talk to you. Thru obtaining some mastery of them, they now become my props with which I pivot around social space.

What person lights his or her first cigarette saying, “I want to be a smoking addict & be compelled to smoke a pack or more a day despite the unpleasant breath, reduced senses of taste & smell, lingering odor, frequent sore throat, & higher risk for all forms of cancer & emphysema”? But, in this day & age, who doesn’t know it comes with a risk when they first inhale? The same is true of alcohol, drugs, sky-diving, driving fast cars — hell, playing football (sorta big in my neck of the woods)! These are all obvious, intuitive. Yes, we play football — “play” is in the very way it is expressed. We don’t say, “I’m going footballing” (well, not in the U.S., at any rate). You get my meaning. So what is qualitatively different about smoking? As Stromberg points out, not much. We start off smoking even though we know it’s bad for us, because, well, probably there are a lot of reasons. Smoking is, Stromberg & his colleagues point out, “socially engineered (advertised) to be an antidote for boredom (Mark Nichter 2003)” (2007:7).

I smoked because it looked cool. I still think some people simply look cool holding & smoking a cigarette, & I thought I was one of them. I stopped but not because I wanted to. It just wasn’t worth it anymore. Same with drugs. Few people smoke a first joint & say, “I want to die a drug addict.” As the authors say, “both drinking and smoking served to structure the unstructured situation of the party through routines of consumption” (Stromberg, Nichter, & Nichter 2007:8). I wanted to know what I was missing, how to be social like those people, how to feel light like they looked, how to feel more comfortable in my own skin, how to be bolder, better, more free, more laid, all that…And it worked. That’s the magic of it. And this is all the exact same thing as boredom. When I’m not bored, I do not think about what I look like to other people or what I might be missing out on because I am busy doing.

Not only does the cigarette or other pivot structure an ambiguous situation, it “promotes social interaction, contributing to an atmosphere of egalitarian comaraderie” (Stromberg, Nichter, & Nichter 2007:9), a factor I also have found to be true. Smoking provides an embodied feeling of belongingness, “something Csordas (1993) has described using the term ‘somatic mode of attention'” (Stromberg, Nichter, & Nichter 2007:11). There was a Friends episode once where Rachel took up smoking so she could go out with her coworkers on smoke breaks, as obviously there was significant bonding & structuring of extrastructural time going on, such that decisions being made in favor of other members of the smoking club in her absence. I distinctly remember this feeling of being part of something, both when I started drinking & smoking. It takes a lot of work for some of us to socialize without a prop when much of the world is oriented around consumption. When I played in bands, the long hours spent sitting in bars after load-in until showtime, including waiting for all the other bands to play, was incredibly fucking boring. In my last band, I used to have to go take walks around the neighborhoods of whatever city we were in while the others sat in the club in some town we’d never been to & drank & smoked. Extrastructural time. What do you do with it? My wife has recently taken up knitting. I get it.

What is so interesting about smoking & drinking to fill these spaces is that they are not innocuous substances. They come with great risk. No one takes the risk without the promise of experiencing something. Gosh, I remember doing incredibly stupid things & remember them with relish. I would never want to take them back & not just because I’d be doomed to do something else stupid & might not be so lucky the next time. Gloriously, ridiculously stupid acts have the potential to be so life-altering. Life-altering things are important things, right? Having kids was life-alteringly important. Getting married was life-alteringly important. And we play at both of those things before they happen. “Play activity is closely patterened after something that already has a meaning in its own terms” (Goffman 1986:40). We play around them because they have tremendous potential import.

Of my late teens & early 20s, I am most proud of what some might have considered the most stupid things I ever did but that in testing the limits of my own capacities were, personally, incredibly important. I used to take multiple hits of acid to see how out of my mind I could get. I remember once being in a predicament wherein I had to drive the half hour home at 4AM thru downtown Indianapolis even though I had lost a reflexive motor sense of how to put the key in, turn on the car, put it in gear, turn the wheel, etc. I felt like I was in a hovercraft going 20MPH & the actions of the car had nothing to do with the actions of my hands & body. Another time I remember walking across a rotted out train trestle in the dark my friends knew about. The next day I saw it was about 100 feet up over a ravine. I wouldn’t do it again, mind you, but I am pleased for that playful night. When I moved to NYC, I used to get smashed drunk & pass out on subways, riding back & forth all night long. One night I kept dozing off & missing my stop, crossing the platform at the next stop to the return train, missing it again. Finally, the car was getting fuller & fuller with people & I ran into some co-workers on their way to work, & there I was still trying to get home. Fortunately, I worked in the music industry where play like that was par for the course. I always say, everything in moderation, even the extremes, which I believe expresses the same principle.

Smoking & drug use are obvious risk behaviors adults play with, but there are many others, more & less obvious. Anything associated with “at-risk” behavior starts as a form of play — sex, body modification, joining gangs, skipping school (which I also did once or twice to play & have fun but was so nerdy at that point I ended up at the library working on a report so I wouldn’t get behind) — but so does joining a cult. I experienced the same awkward nervousness upon entering a Pentecostal revival meeting in my first anthropological research endeavor but ultimately enjoyed playing at praying & the charisms, which make for fantastic pivots (if you can’t think of what to do or say, just shout “Jesus!”). Not that I am calling Pentecostalism cultish, but they both provide compelling props to fill all manner of interstitial spaces & can really string you out & take over your life, for better or worse. As Stromberg et al. point out, play is what we do in those periods of our day that are not scheduled, wherein we have no plans for our minds or bodies. These are the chunks that the religions like to get hold of, to give us some more structure/ritual, these are the “idle hands” moments.

Probably most of the time such pivotal exploration is adaptive, or it would not be so ubiquitous. Sometimes it is maladaptive. We poke at the fire, we see if it burns. We smoke a cigarette, we take a drink, we eat a potato chip, we push the envelope to see what will happen. Sometimes kids doing stupid things while on acid or drunk get killed, sometimes smokers get cancer & die, sometimes people who use potato chips as props grow obese & contract type II diabetes & cardiovascular disease…right? Sometimes. So I would say, for instance, that someone who sky-dives or bunjie-jumps or drives race cars is no more crazy than someone who smokes cigarettes or plays with a smartphone. It’s all on a continuum of playing with risk.

Now, back to smartphones. What is risky about them? I don’t know. This is not a neat & tidy unitary theory where play = risk or anything like that. A smartphone in the hands of a student while you’re teaching class is certainly a prop that they’re playing with because they’re bored or stressed or something. I learned a trick from a colleague to bribe the students to keep the phones put away. The whole class gets an increasing amount of extra credit on the final if no one pulls one out all semester, but if one person violates that, everyone loses. It’s like Full Metal Jacket, where Pyle eats the donut while the whole platoon does push-ups as punishment for his error. You remember what they did to Pyle? Then he went postal. So if you pull your goddamn smartphone out my class again…

Pingback: Are Smartphones Making Us Dumber? | big REDefined

Pingback: 2012′s Cheap Thrills thru Evolution in Review | Welcome to the EvoS Consortium!

Pingback: Les smartphones ont-ils tué l’ennui ? | InternetActu

Pingback: El asesinato del aburrimiento | SinapSit

Pingback: Time Management Skills | Welcome to the EvoS Consortium!

Pingback: News | Ripple's Web » Smartphones, slayers of boredom

Pingback: EBW MAGAZINE – Have smartphones killed boredom (and is that good)?

Pingback: Have smartphones killed boredom?- @helmirofiq

Pingback: News | Ripple's Web » Smartphones conquer boredom. At what cost?

Pingback: Have smartphones killed boredom (and is that good)? – CNN | Latest News & Headlines

Pingback: News | Ripple's Web » Have smartphones killed boredom?

Pingback: Ripley's Blog | Ripple's Web » Have smartphones killed boredom?

Pingback: Do smartphones kill boredom? | News from around the world

Pingback: This and that | Ripple's Web » Have smartphones killed boredom?

Pingback: Smartphones conquer boredom, but at what cost?- @helmirofiq

Pingback: Remember How I Said Blogging is Totally Rad? | Anthropology Blog Network

Pingback: Smartphones conquer boredom, but at what cost? | iPhone Developers

Pingback: News | Ripple's Web » Smartphones conquer boredom, but at what cost?

Pingback: Have smartphones killed boredom (and is that good)? | PC Tech Magazine

Pingback: Have smartphones killed boredom? | Latest News & Headlines

Pingback: GlassTV – Have smartphones killed boredom (and is that good)?

Pingback: Have smartphones killed boredom? | News from around the world

Greg Downey just posted this link re “Play, Stress, and the Learning Brain” from the Dana Foundation site over on the Neuroanthropology Interest Group on Facebook. I wish I’d done a little more homework like reading this before I took a call from a CNN.com reporter re smartphones & boredom today. http://dana.org/news/cerebrum/detail.aspx?id=39402

Just found this related post by fellow blogger Rose Chang from last year: http://evostudies.org/2011/09/childhood-risky-play-and-overprotective-parents/

Hi Peter,

That (expectation of/conditioning for arousal) makes perfect sense to me & would seem to be the missing conceptual & physiological link. Obviously, I need to read your book when I have a chance to see what else you have already explained re my ponderings. I am wondering if this theoretical (& methodological?) approach will be useful in a study we’re currently doing of tattoo behavior in college students…Playing with body projects & identity…

Hi Chris,

There’s much of interest here, I’ll just respond to one point. Some of the research on ADHD suggests that we come to expect a certain level of emotional and cognitive arousal based on what we encounter in the environment, and that the increased rates of this disorder are rooted in the fast-paced, electronically saturated environment of contemporary society. That is, the more arousal you have come to expect, the more you need to fend off discomfort and dysfunction.

If this is true, then it may be useful to think of boredom as a form of withdrawal from expected or desired levels of arousal. The analogy here is, of course, to withdrawal from a psychoactive chemical, except that perhaps it’s not an analogy.

I think risk, as you say, isn’t intrinsic to play, it’s just that risk is an enormously powerful source of arousal. But even the most innocent, non-risky, social interaction can be arousing. (I’ve got a text!). So, in sum, I suspect that one driver of all this (and only one) is simply the homeostatic processes of nervous arousal in our society.