The December 2012 issues of Smithsonian Magazine had a fire theme, & archaeologist Thomas Wynn contributed a short piece on the influence of fire in the evolution of the human mind. He briefs the work of three researchers doing work I didn’t know about–John Gowlett, Frederick L. Coolidge, & Matt Rossano–including one (Rossano) whose book on the evolution of religion (Supernatural Selection) has actually been sitting on my shelf to review for a course for over a year. I pulled some of their relevant articles & began reading, starting with Gowlett’s 2006 piece, “The early settlement of northern Europe: Fire history in the context of climate change and the social brain” in Comptes Rendes Palevol.

Dr. Gowlett is British archaeologist & one of the directors of the Archaeology of the Social Brain project. This paper considers two hypotheses to explain the distribution for fire manipulation by humans around 0.4 million years ago–(1) that inconsistent evidence for fire manipulation at sites from this time period are due problems of preservation & past climate change or (2) that changes in human social network size increased human abilities to exploit certain environments in tandem w/ & via increased language capacity & associated socio-technical skills like fire management (2006:300). The issue revolves around the sudden appearance of concentrations of early fire evidence at sites around the Middle Pleistocene, 400kya, scattered throughout Europe, but there is a good chance that earlier evidence could have been eradicated through glacial processes. Is this sudden but not uniform concentration evidence of the elaboration of socio-technical skills & the social brain or what wasn’t wiped clean?

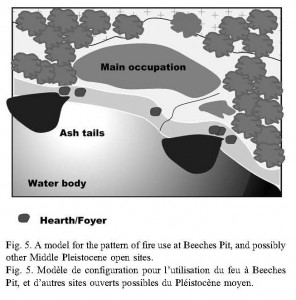

A model for the pattern fire use in hearths at Middle Pleistocene sites based on Beeches Pit (Fig. 5, Gowlett 2006)

Beeches Pit in East Anglia, UK is an example of a Middle Pleistocene site that has yielded extensive evidence of hominid occupation, including abundant evidence of fire use, including burnt flints & what have been interpreted as hearths. Multiple hearths are separated at two stratigraphic levels in a context near the edge of a body of water, suggesting the strategic placement with water on one side & dead-wood fuel on the other. Large tails of burnt material suggests prolonged fires, which may because hominids had not yet mastered kindling fires & had to keep them going. Modern evidence suggests that this is not due to forest fires, as they are rare, only return to the same areas every 10-300 years, & are even more rare along water courses.

Although there is no evidence for controlled fire use of this type in Northern Europe prior to 500kya, there is evidence at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov in Israel ca. 700kya & possibly in Africa at Chesowana ca. 1.4mya. This suggests that the lack of evidence in Northern Europe may be due to climatic conditions. However, the social brain hypothesis places changes in brain size at 500-300kya, which would coincide with this appearance of controlled fire use in Northern Europe & be consistent with theories of enhanced network size & language evolution at this point. The larger brains & larger network sizes would “impose larger ‘managing’ loads on the brain,” the costs of which would be met by higher grade diets & reduced guts, made possible thru cooking.

Although there is evidence of increased cranial size from Atapuerca & Ceprano associated with Homo, there is no corresponding model for “proto-fire-use.” In other words, what was the spark (pun intended) that put these larger brained hominids onto fire use? Gowlett’s tentative scenario is that

fire use became advantageous at an early date, for reasons of adaptation to climate, and extension of diet, but that perhaps early humans could control it only in particular circumstances. This would expalin why so many early sites have no fire evidence… (2006:306)

Earlier fire use may have afforded benefits, but if kindling was not mastered, its use would be driven by climatic conditions. In temperate conditions, the cost of letting the fire go out was low. In cold conditions like that encountered in Northern Europe at the edges of the glacier areas, the cost would be high, perhaps stimulating a division of labor to tend the fire & bring fuel. Thus, systematic fire use without knowledge of kindling would require strong social networks, issues that had been effectively resolved by 40kya.