Redrawn from my notes. I believe Larry developed this model, but I am not 100% sure. I suppose I could ask him.

This semester I redesigned the graduate-level physical anthropology course I teach. Last time around (which was the first time teaching a full-on grad course for me), I taught it as a seminar, based largely around my predecessor Professor Emeritus Jim Bindon‘s syllabus, in that there were articles or book chapters assigned each class with the expectation that we would all discuss them. There were four in-class essay exams designed to simulate the comprehensive exams. Occasionally, I opted to divide the class into groups for activities around the readings, such as debating whether “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis) was more ape-like or human-like. Ultimately, however, I found the course boring to teach (as is always the case when I try to take short cuts by adopting someone else’s course) & figured it must have been unsatisfying for the students as well. Their performance on the comps suggested as much.

This semester, I switched the reading material completely (here is a link to the current syllabus). I used Muehlenbein’s edited Human Evolutionary Biology, Ciochon & Fleagle’s Human Evolution Source Book, Ciochon & Nisbett’s Primate Anthology, chapters from Konner’s The Evolution of Childhood, & miscellaneous readings from Mark Cohen & John Relethford. It was a lot of reading for each 3-hour meeting, but I divided he readings up & assigned them in sets to pairs of students, whose responsibility was to summarize the readings as blog posts & prepare in-class presentations. In addition to a presentation, I told them to prepare something else to help us integrate the material, either a supplementary but related reading or an activity. I don’t think a single supplementary reading was presented all semester, but the students came up with a number of awesome activities, which I will be blogging about here in the near future. By & large, I think it went great. We covered far more material than I’ve ever covered in a course, had lots of great discussions, & had a lot of fun with the activities. But I do think some of the readings can be changed or cut, & I would like to share a few of my thoughts for my own future reference & that of anyone who might like to try a similar format.

Some of the chapters in Human Evolutionary Biology are, of course, more useful to a given class than others. The text is in many ways similar to Stinson et al.’s Human Biology, which just came out with a revised edition this year. There are several chapters in Human Biology that I prefer to counterparts in Muehlenbein’s volume, there are a few chapters on the same topic by the same authors in both, & there are several excellent chapters on topics in Human Evolutionary Biology that aren’t dealt with at all in Human Biology, such as sections on human sexuality & evolutionary medicine. For instance, we found the Jones chapter “Demography” to be fairly uninformative in terms of introducing the basic concepts of demography, where I was expecting something like Gage’s chapter in Human Biology (& which would have also been easier to teach, as Tim Gage was my professor when I took the analog to this course–in fact, the new edition has a revised chapter written by Gage & my friend Sharon DeWitte, who I also TA’ed for as a grad student). There are, however, more chapters in Human Evolutionary Biology than can be covered in one semester, as there is absolutely no attention paid paleoanthropology or primatology. So, unless one is teaching a purely human biology-oriented course, you have to supplement & therefore can’t cover the whole book. I would actually have preferred to use the Human Biology volume with the Human Evolution Source Book & Primate Anthology for that reason, except for the cost. Human Biology is only in hardcover costs over $100, whereas Human Evolutionary Biology is a paperback that costs less than $40.

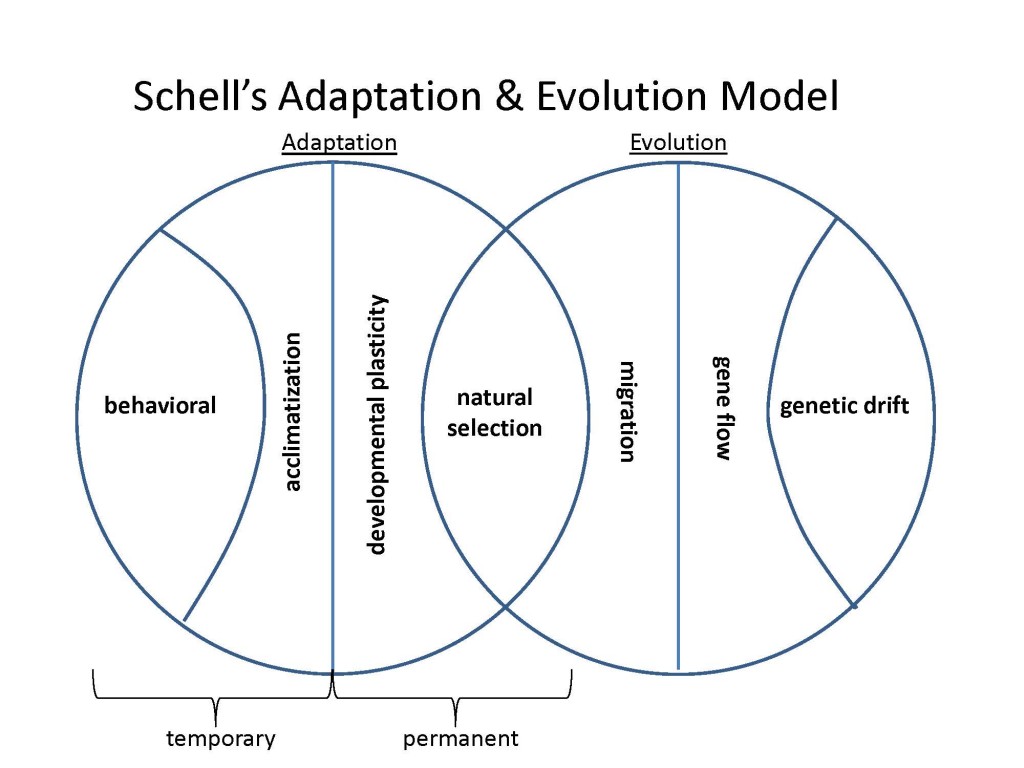

Though we covered a lot of ground, we may have covered too much, at the expense of failing to impress upon them some of the major overarching concepts. Specifically, I think the concept of adaptation is so second-nature to me that I let it go as implied where I should have been heavier-handed about it. We read several articles that discussed it indirectly, & I shared Larry Schell‘s evolution/adaptation model, but we did not read a good article specifically on the adaptation concept. In the future, if I’m going to test students on the adaptation paradigm (which I will), I need to assign the Frisancho chapter “The Study of Human Adaptation” & not fizzle out before the Kuzawa chapter “Beyond Feast-Famine: Brain Evolution, Human Life History, & the Metabolic Syndrome.” I should also assign Gould & Lewontin’s classic “The Spandrels of San Marcos & the Panglossian Paradigm” & Schell’s “Human Biology Adaptability with Special Emphasis on Plasticity.” In a book about human evolution, it is nevertheless useful to have pieces that are cautious if not critical of the adaptationist paradigm. The only piece in Human Evolutionary Biology that I would consider even cautious is Brutsaert’s piece on high altitude adaptation. Since I took courses with Brutsaert & Schell (my advisor) in grad school, I know these pieces would provide what I, in retrospect, would have liked to better convey.

John Hawks’ lectures during the last week of classes were clearly influential. In particular, students referenced his discussion of the increased human evolution during the Holocene, including the classic sickle cell & lactase persistence examples he discussed in some detail. While we talked about sickle cell, I opted not to cover lactase persistence. However, they really should be part of the basic human evolution story that every grad student in anthropology knows. At the recent American Anthropological Association conference, there was a session about crossing disciplinary boundaries between anthropology & genetics, & I was rather horrified that one of the geneticists, despite some apparent anthropology training, had no idea who Frans Boas was. And even more horrifying, he was sitting next to his post-doc advisor, who did not seem bothered by this. Okay, so not every human geneticist should be expected to be trained in 4-field Anthropology, but you really should be familiar with the most famous & significant individual associated with the conference at which you are speaking. Just sayin’. So, I think I would be pretty embarrassed if my students couldn’t at least, at some point down the road, say, “I think we talked about that in our ‘Principles of Physical Anthropology’ course in grad school”…

Finally, I assume grad students know how to write an essay, & I’m willing to give them the benefit of the doubth that they actually do, but I suspect they don’t revisit the principles of essay-writing before putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard, as it were). I recall my own experience in grad school, arrogantly thinking that because I was considered such a good writer as an undergrad, this would automatically translate to graduate writing. It doesn’t. What was pretty, expressive writing as an undergrad (& I was the rare student who actually proofread & paid attention to the automated spell/grammar-check Microsoft Word provides) translated into meandering narratives with unwelcome suspense & a complete lack of depth or closure (sort of like my blogging!). Graduate essays are not meant to be edge-of-your-seat whodunnits. I need to invoke my graduate advisor (the aforementioned Larry Schell) & tell my students what he repeatedly told us when we had to write essays for him: “Say what you’re going to say. Say what you’re saying. Say what you said.”

Start with an outline. Why is everyone so seemingly averse to outlines? Do they think the few minutes it takes to outline will carve precious seconds off their lives? Maybe it’s an in-class essay & you’re under the gun, but–trust me–it will help immensely if there’s enough detail in it to save you from the meandering narrative (i.e., avoid the “oh-yeah-&-I-forgot-to-mention-this-earlier-but”…). If it’s an out-of-class essay, type your outline. Then you can just plug your examples in the right places, turn fragments into sentences, fix your punctuation, remove the outline formatting &–voila!–you have an essay. This is not creative writing, folks–it is a formula, as follows:

- Introduction: “Say what you’re going to say.” If it’s an essay exam, the question already tells you what you’re going to say, so reiterate it. Remove the question marks & turn them into statements. You have should at least 3 topics to give your essay structure. Remove the mystery by telling the reader what they’re going to be reading. Then add your own piece by WRITING A THESIS STATEMENT. Why do so many students forget this fundamental of essay writing?

- Body: “Say what you’re saying.” If you have 3 topics, then you should have 3 sections (which doesn’t mean 3 paragraphs). Each paragraph should start with a sentence that is the lead idea for the paragraph. DON’T BURY YOUR LEAD. Your reader shouldn’t have to wade 3 sentences deep to get to your point. Your point is your lead. The rest of the paragraph elaborates on that lead. Do you remember how you were taught to power-skim by just reading the first sentence of each paragraph? You should be able to do this with your essay & get the gist of the whole thing. If it’s a new & important idea that you’re going to talk more about, new paragraph. On the other hand, don’t introduce a new idea or concept in the last sentence of a paragraph then just leave it hanging. And be sure to cite everything. No paragraph in the body should be without citations. Paragraphs without citations say, “I’m speculating because I haven’t read the material or am just winging it from memory & not willing to look anything up.” The exception to this rule is in-class essays, where you don’t have access to the sources or have been told not to worry about citations. Otherwise, UNLESS TOLD NOT TO WORRY ABOUT CITATIONS & REFERENCES, ALWAYS include citations & references. And learn the style for your discipline. Better yet, if you get to take the essay home & type it, get yourself some bibliographic software. You won’t even have to learn styles because these software packages automate citing & referencing for you. My university provides free access to RefWorks. Zotero is also available free & open-source (though when last I used it didn’t have the American Anthropological Association style that I use most). There are numerous others. This will save weeks of your life if you continue in academia, once you get over the rather small learning curve.

- Conclusion: “Say what you said.” A conclusion should summarize the essay, not just be a few tacked-on sentences (which say to your reader, I’m tired of writing–here is a stop sign). If you wrote paragraph leads, you should be able to go back & reiterate them. Then you can add a remark about unanswered questions or issues that are still open to debate with regard to the argument you’ve proposed or point to ongoing or future research being conducted. However, you should have mentioned these along the way. The conclusion is not the place to introduce any new data. Finally, at the end of this is where that concluding statement goes.

- By now, you should be up to your suggested page-count. Hopefully, you’re a bit over it, in which case you can do some editing, clean up your prose, whittle out redundancies, & turn in some crisp writing. If you’re allowed to write 4 pages & you’ve only written 3, there are probably some things you mentioned that you could explain better to show how well you’ve truly integrated the material or something important (another source perhaps) that you’ve left out altogether.

Now the trick is to remember to reread this in 3 years before I teach this course again!